If you’re planning a trip to Iceland, you’ll quickly discover the country’s food scene is as unique as its landscapes. At least that is what we found. From cosy bowls of fish stew after a day in the Westfjords to lobster pizza in a South Coast fishing village, eating here is an adventure in itself. Icelandic cuisine draws on centuries-old traditions shaped by isolation and survival, then adds modern creativity from a new generation of chefs.

On this trip, you might start with plokkfiskur, a creamy fish stew, or hangikjöt, the smoky lamb often served at Christmas. You’ll find pylsur, the famous Icelandic hot dogs, in both city streets and remote gas stations, while rúgbrauð (rye bread) bakes underground in hot springs. Fresh catches like humar (lobster) and Arctic char showcase the island’s pristine waters, and treats like homemade Icelandic ice cream or tangy skyr give a sweet finish to any day.

Our guide takes you through the most iconic and delicious Icelandic foods to try, from hearty farmhouse favourites to inventive dishes in Reykjavík’s buzzing food scene.

Top Iceland Foods at a Glance

Plokkfiskur – Creamy fish stew served with dark rye bread

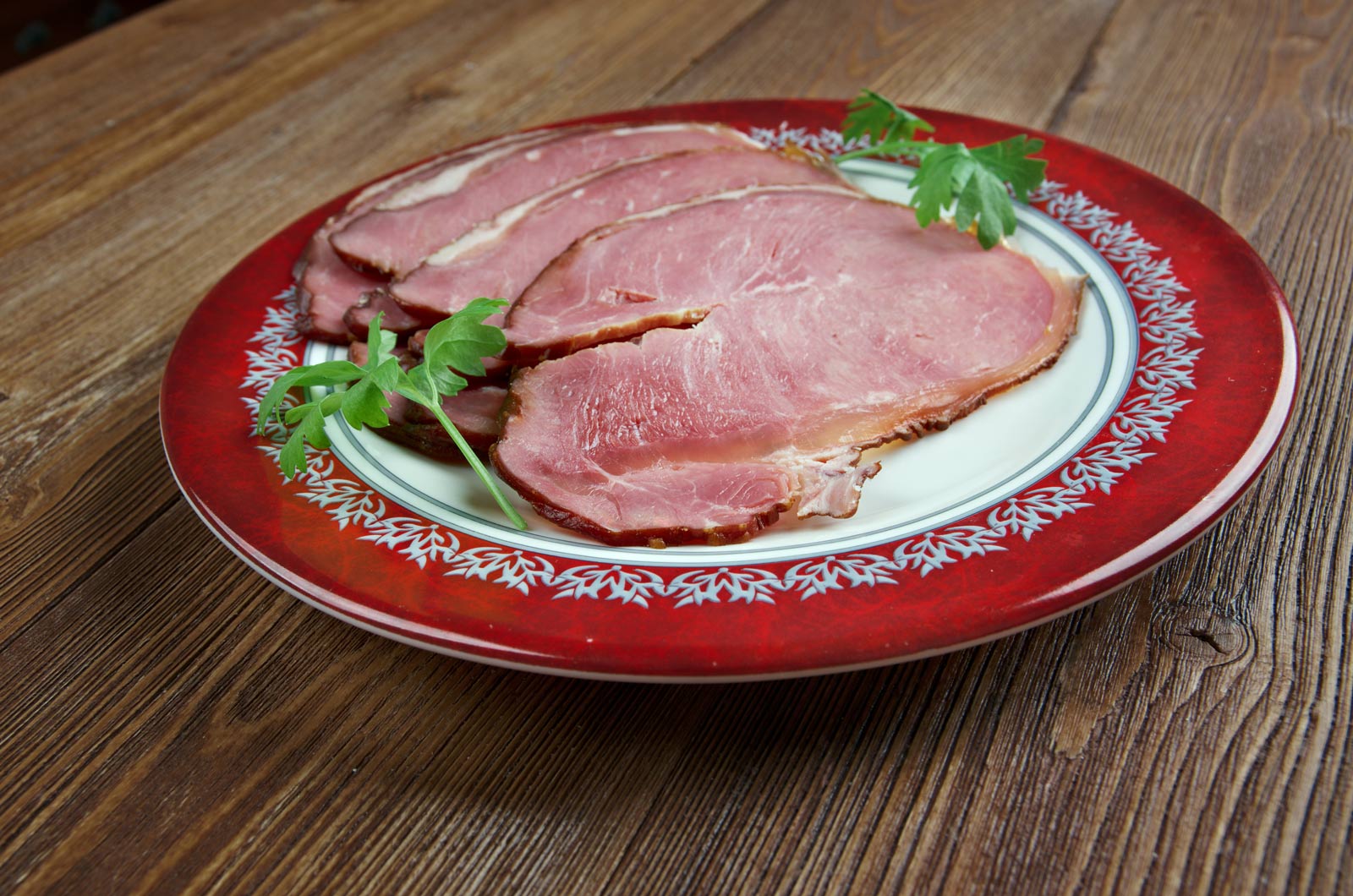

Hangikjöt – Smoked lamb, often a Christmas tradition

Pylsur – Icelandic hot dogs with fried onions and remoulade

Humar – Sweet lobster tails from the South Coast

Rúgbrauð – Rye bread baked in hot springs

Skyr – Thick yogurt eaten at breakfast or in desserts

Why Iceland’s Food Scene is Unique

Iceland’s volcanic soil, cold seas, and geothermal resources have shaped its cuisine for over a thousand years. Farming is limited, so lamb, dairy, and seafood became staples. Geothermal greenhouses now grow vegetables like tomatoes and cucumbers year-round, while the surrounding ocean provides cod, haddock, and Arctic char. The result is a blend of traditional recipes, often born out of necessity, and modern dishes inspired by global culinary trends.

One night you might tuck into lamb soup at a mountain hut; the next, you’re sipping craft beer with langoustine tacos in Reykjavík. For a true Iceland foodie experience, try both ends of the spectrum.

1. Pylsur – Famous Icelandic Hot Dog

What it is:Pylsur are Iceland’s famous hot dogs, made from a blend of lamb, pork, and beef. They’re served in a bun with raw onions, crispy fried onions, tangy mustard, sweet ketchup (made with apples), and creamy remoulade.

Why try it:We stood in the snow outside Bæjarins Beztu Pylsur in Reykjavík, the country’s most famous hot dog stand , and it was worth every minute of the wait. The lamb gives the sausage a subtle sweetness, while the fried onions add a satisfying crunch.

Cultural note:Hot dogs became popular in Iceland after WWII, and today they’re considered a national fast food. They’re also one of the most affordable meals you can find in this otherwise expensive country.

Where to find it:Bæjarins Beztu Pylsur is the iconic spot, but you’ll find pylsur at gas stations, festivals, and roadside stands nationwide. Order it “ein með öllu” — one with everything.

2. Skyr – Icelandic Yogurt

What it is:Skyr is a thick, protein-rich dairy product that looks and tastes similar to Greek yogurt but is technically classified as a soft cheese. The Icelandic version is made by straining milk to remove the whey, it has a creamy texture and a tangy flavour that pairs perfectly with fruit, honey, or granola.

Why try it:On our glacier hike day in Vatnajökull National Park, we packed individual pots of skyr for breakfast. It was filling enough to keep us going for hours without weighing us down, and the tangy creaminess was refreshing after the long drive. It’s not just a healthy snack — it’s a true food from Iceland that locals enjoy daily, whether at home or on the go.

Cultural note:Skyr has been part of Icelandic diets for over a thousand years, dating back to Viking settlements. Once made exclusively in homes and farms, it’s now produced commercially but still uses traditional cultures to maintain its distinct flavour.

Where to find it:Every supermarket, café, and convenience store sells skyr in plain and flavoured varieties. For a special treat, try skyr-based desserts like skyrkaka (cheesecake) in restaurants.

3. Plokkfiskur – Icelandic Fish Stew

What it is:Plokkfiskur is a creamy stew of flaked white fish (usually cod or haddock), mashed potatoes, onions, and a buttery white sauce. The name literally means “plucked fish,” describing the way the fish is broken into small pieces before mixing.

Why try it:We first had plokkfiskur in a harbour café in Ísafjörður on a snowy winter night. The windows steamed up as locals came in from the cold, and the smell of fish stew filled the air. It’s hearty without being heavy, and the sweet, fresh fish balances perfectly with the buttery sauce.

Cultural note:This dish started as a way to use leftover fish, stretching it with potatoes to feed the whole family. Today, it’s comfort food — the kind you’ll find at home kitchens, roadside cafés, and upscale restaurants alike.

Where to find it:In Reykjavík, Café Loki serves a traditional plokkfiskur with dark rye bread. Coastal towns like Siglufjörður and Húsavík have excellent versions in their harbourside restaurants. You can even buy it pre-made in grocery stores if you’re self-catering.

4. Kjötsúpa – Lamb Stew

What it is:A hearty soup made with lamb shank, root vegetables like carrots and rutabagas, potatoes, and fresh herbs.

Why try it:On a cold, windy day along the Golden Circle, we stopped at a small café and ordered steaming bowls of kjötsúpa. The lamb was so tender it fell off the bone, and the broth was rich without being heavy.

Cultural note:Kjötsúpa is one of the most Icelandic typical food dishes, valued for its ability to warm and nourish through long winters.

Where to find it:Restaurants, countryside guesthouses, and even gas station cafés.

5. Hangikjöt – Smoked Lamb

What it is:Hangikjöt translates to “hung meat,” referring to the way the lamb is smoked while hanging over a birchwood or dried sheep dung fire. This traditional preservation method infuses the meat with a deep, smoky flavour.

Why try it:We first tried hangikjöt during the Christmas season in Reykjavík, served with boiled potatoes, green peas, red cabbage, and Icelandic leaf bread. The smoky aroma hit before the plate reached the table, and the meat was so tender it practically melted.

Cultural note:Sheep farming has been central to Iceland’s economy for centuries. Smoking lamb wasn’t just about taste, it was about survival through the long winters. Even today, hangikjöt is a festive centrepiece, especially in December.

Where to find it:Available in grocery stores during the holidays and in traditional restaurants year-round. Farm stays sometimes serve their own smoked lamb, which is about as authentic as it gets.

6. Humar – Icelandic Lobster

What it is:Humar is Iceland’s small, sweet lobster, actually closer to langoustine, prized for its tender tail meat. It’s served grilled, baked, fried in garlic butter, or in creamy lobster soup called humarsúpa.

Why try it:On our South Coast road trip, we stopped in Höfn, Iceland’s lobster capital, for humar pizza. The sweet lobster meat with melted cheese and herbs was an unforgettable combination.

Cultural note:Humar is mostly caught along Iceland’s southeast coast, and fishing for it is strictly regulated to ensure sustainability.

Where to find it:Seafood restaurants in Höfn and Reykjavík serve humar in various forms, from gourmet entrées to casual lobster rolls.

7. Rúgbrauð – Hot Spring Rye Bread

What it is:Rúgbrauð is a dense, dark rye bread with a slightly sweet flavour, traditionally baked in the ground using geothermal heat from Iceland’s hot springs. The dough is placed in a pot or wooden cask, buried near a hot spring, and left to cook slowly for about 24 hours using geothermal heat.

Why try it:We first tasted Icelandic rye bread fresh from the earth at Laugarvatn Fontana, where staff dug up steaming pots right in front of us. The bread was moist, rich, and subtly sweet, so good it barely needed butter. Pairing it with smoked lamb or pickled herring is a classic Icelandic combination.

Cultural note:Before ovens were common, Icelanders relied on the earth’s natural geothermal heat to cook. Rúgbrauð (aka Hot Spring Bread) was a staple because it could be made year-round without scarce fuel resources.

Where to find it:Bakeries and cafés across the country sell rúgbrauð, but for the authentic experience, visit Laugarvatn Fontana or other hot spring towns where you can watch it being baked underground.

8. Harðfiskur – Dried Fish

What it is:Harðfiskur is dried fish, typically cod, haddock, or wolffish, cured in the salty North Atlantic air until it’s chewy and packed with flavour.

Why try it:On a road trip through the Westfjords, we grabbed a bag in Bolungarvík, thinking it would be a light snack. Within minutes, we were hooked, especially after locals told us to spread it with salted butter. It’s protein-rich, portable, and one of the most traditional foods from Iceland.

Cultural note:Drying fish dates back over 1,000 years and is similar in principle to aging cheese. In many fishing villages, you’ll still see wooden racks lined with fish drying in the open air.

Where to find it:Sold in grocery stores, gas stations, and harbour markets. For the freshest, buy it directly from fishermen in coastal towns.

9. Arctic Char

What it is:A cold-water fish native to Iceland, Arctic char is somewhere between salmon and trout in flavour and texture. It can be grilled, smoked, or pan-seared.

Why try it:We had Arctic char in Seyðisfjörður, butter fried with tomatoes and sliced almonds. The fish was buttery and delicate, with a clean, fresh taste that spoke to its pristine environment.

Cultural note:Arctic char thrives in Iceland’s cold, clean rivers and lakes, making it a reliable food source for centuries.

Where to find it:Served at restaurants across Iceland, especially in the Eastfjords and other fishing regions.

10. Fish and Chips – Iceland Style

What it is:Fresh cod or haddock coated in a light batter, fried until crisp, and served with chunky fries and homemade sauces.

Why try it:In Akureyri, we tucked into fish and chips where the cod had been caught just hours earlier. The fish flaked apart with the lightest touch of a fork, and the tartar sauce was bright with fresh herbs.

Cultural note:While fish and chips isn’t native to Iceland, the quality of the fish here makes it exceptional. Icelandic waters produce some of the best cod in the world.

Where to find it:Harbour cafés, Reykjavík’s Icelandic Fish & Chips restaurant, and coastal food trucks.

11. Flatkaka með Hangikjöti – Flatbread with Smoked Lamb

What it is:Flatkaka is a thin, round flatbread made from rye flour and water, cooked quickly on a hot griddle. It’s often topped with hangikjöt (smoked lamb), cream cheese, or lamb liver pâté.

Why try it:We tried flatkaka at a family-run café on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula, where it was served warm with thick slices of smoky lamb. It’s simple but full of flavour, and it’s one of those Iceland foods to try that you can easily recreate at home.

Cultural note:Flatbreads have been part of Icelandic diets for centuries, offering a quick, filling base that could be paired with whatever was available, from lamb to fish to foraged herbs.

Where to find it:Available in most bakeries and supermarkets. Many guesthouses serve it as part of a traditional breakfast spread.

12. Icelandic Mussels

What it is:Fresh mussels harvested from Iceland’s clean coastal waters, often steamed with garlic, herbs, and white wine.

Why try it:In Stykkishólmur, we had a steaming pot of mussels caught that morning in Breiðafjörður Bay, sweet, briny, and absolutely fresh.

Cultural note:Iceland’s cold waters slow the mussels’ growth, resulting in a more concentrated flavour.

Where to find it:Coastal seafood restaurants, especially in the Westfjords and Snæfellsnes Peninsula.

13. Pickled Herring

What it is:Marinated herring fillets preserved in vinegar, sugar, and spices, often served with warm rye bread, boiled potatoes, and sometimes hard-boiled eggs.

Why try it:We had pickled herring for breakfast at a harbour café in Ísafjörður, and the combination of sweet-sour fish with warm, earthy rúgbrauð was unforgettable. It’s simple, satisfying, and deeply rooted in Iceland’s coastal traditions.

Cultural note:Herring fishing was once a major part of Iceland’s economy, and preserving it through pickling meant it could be enjoyed year-round.

Where to find it:Breakfast buffets, fish markets, and traditional restaurants.

14. Icelandic Ice Cream

What it is:Icelanders have a surprising obsession with ice cream — and they eat it year-round, even in snowstorms. It ranges from soft-serve ice cream (known as “ís”) dipped in chocolate to artisanal scoops in inventive flavours like rhubarb, licorice, and even beer.

Why try it:We once stood in line for Icelandic ice cream in Reykjavík while the wind chill was well below freezing, and we weren’t the only ones. The creamy texture, rich flavour, and generous toppings made every shiver worth it. It’s one of those Iceland foods to try that tells you as much about the culture as it does about the cuisine.

Cultural note:Ice cream parlours are a social hub in Iceland. Families, friends, and couples often make a night of going out for ice cream, no matter the weather.

Where to find it:Popular spots include Valdís in Reykjavík for creative flavours and Ísbúð Vesturbæjar for classic soft-serve with mix-ins.

15. Icelandic Cinnamon Roll (Kanilsnúðar)

What it is:Kanilsnúðar are Iceland’s take on the cinnamon roll, soft, buttery dough spiralled with cinnamon sugar and often topped with a drizzle of icing or a dusting of coarse sugar.

Why try it:We followed the scent of fresh-baked cinnamon rolls to Brauð & Co. in Reykjavík, and within minutes we were unravelling the warm, sticky spiral. The combination of pillowy dough, fragrant cinnamon, and just the right amount of sweetness makes it one of the best good food in Iceland moments for anyone with a sweet tooth.

Cultural note:While inspired by Scandinavian baking traditions, Icelanders have made kanilsnúðar their own. They’re as popular for breakfast as they are for an afternoon treat.

Where to find it:Bakeries across Iceland, especially Brauð & Co. and Sandholt in Reykjavík, serve freshly baked cinnamon rolls daily.

16. Icelandic Cheese & Dairy

What it is:While skyr gets most of the international attention, Iceland’s dairy scene offers a variety of unique cheeses. These include tangy skyr-based spreads, soft white cheeses, and brunost (Norwegian-style brown cheese) made from caramelized whey, which has a sweet, nutty flavour.

Why try it:We stumbled upon a cheese counter at Reykjavik’s Kolaportið flea market and couldn’t resist sampling everything. The brunost was unlike any cheese we’d tasted before, almost dessert-like, while the soft cheeses were rich and creamy, perfect with rye bread or crackers.

Cultural note:Dairy farming has been a cornerstone of Icelandic agriculture for over a millennium. Even in the harshest conditions, sheep and cows provided milk that could be turned into cheese, butter, and skyr to last through the winter.

Where to find it:Specialty food shops, markets, and cheese plates in Reykjavík wine bars. Many rural guesthouses serve their own farm-made cheese.

17. Hákarl – Fermented Shark

What it is:Greenland fermented shark meat is fermented for several months and then dried, resulting in a strong aroma and intense flavour.

Why try it:We sampled hákarl at a fishing village museum in Húsavík. The smell was eye-watering, but chasing it with Brennivín (Iceland’s schnapps) made the experience more fun than frightening. Let’s just say some local foods are fun to try once.

Cultural note:Fermented shark was developed as a survival food; Greenland shark is toxic when fresh, so fermentation was necessary to make it safe.

Where to find it:Specialty shops, Þorrablót feasts, and traditional restaurants.

18. Icelandic Craft Beer & Brennivín

What it is:Iceland’s craft beer scene offers a surprising variety, from crisp Arctic lagers brewed with glacial water to rich stouts flavoured with local herbs. Brennivín, on the other hand, is a clear schnapps infused with caraway seeds. Its nickname, “Black Death,” comes from the black label used when it was first produced, and its strong, distinctive taste.

Why try it:We had our first taste of Brennivín as part of the classic “hákarl challenge” in Reykjavík — the schnapps’ bold, spicy flavour cut right through the fermented shark’s intense aroma. Pairing a cold craft beer with fresh humar or lamb stew is equally rewarding, adding a local touch to any meal.

Cultural note:Beer was banned in Iceland from 1915 until March 1, 1989; a date still celebrated as “Beer Day.” Since then, breweries have flourished, creating beers that reflect Iceland’s unique ingredients and pure water sources. Brennivín remains tied to tradition, often served at Þorrablót feasts and other cultural gatherings.

Where to find it:Sample craft beer at Reykjavík brewpubs like Skúli or MicroBar, or visit local breweries in towns like Akureyri and Egilsstaðir. Brennivín is sold at Vínbúðin liquor stores and served in most traditional restaurants and bars.

Exploring the Icelandic food scene is like taking a bite out of the country’s history, landscape, and culture all at once. Every dish, whether it’s a simple slice of rye bread fresh from a hot spring or a plate of humar in a seaside café, tells a story of resourcefulness, tradition, and pride in local ingredients.

From hearty staples like lamb soup and fish stew to sweet comforts like skyr and cinnamon rolls, there’s something for every palate. And with modern Icelandic chefs reimagining these classics, there’s never been a better time to be an Iceland foodie.

So, as you plan your trip, make room in your itinerary (and your stomach) for these iconic flavours. Whether you’re sipping Brennivín with locals at a midwinter festival or grabbing a hot dog at a Reykjavik food stand, you’ll leave with more than just great photos, you’ll take home the taste of Iceland.

FAQ – Icelandic Food

Pylsur, Iceland’s hot dogs, are often called the national dish. They are made with lamb, pork, and beef and topped with raw onions, crispy onions, mustard, apple ketchup, and remoulade. Try the original stand in Reykjavík at Bæjarins Beztu Pylsur.

Start with plokkfiskur fish stew, kjötsúpa lamb soup, hangikjöt smoked lamb, rúgbrauð hot spring rye bread, harðfiskur dried fish, skyr, and humar langoustine. These classics reflect Iceland’s preservation traditions and local ingredients.

Eating out can be pricey. For value, grab hot dogs, bakery items, or supermarket picnic supplies and mix in a few sit?down meals. Government?run liquor stores have limited hours, so plan ahead if you want local beer or Brennivín.

Visit Laugarvatn Fontana to see bread buried in geothermal sand and baked for about 24 hours, with daily tastings and demos.

On March 1, 1989. The date is still celebrated nationwide as Beer Day.

Look for specialty shops and museums that offer samples, and seasonal Þorrablót events. It is commonly served with a shot of Brennivín.